Full U.S. energy loan chief interview: utilities, hydrogen and more

Latest News

WASHINGTON — The headquarters of the United States Energy Department is located in a stocky, sprawling building — technically the architectural style is “brutalist.”

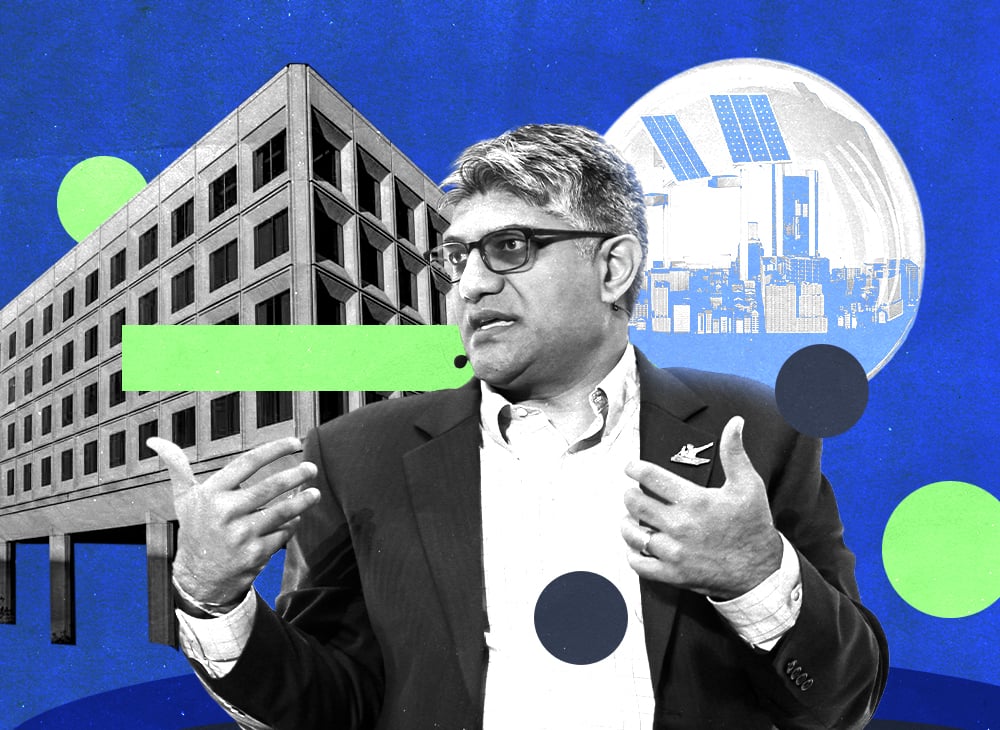

If a structure could embody intransigence, this one would. Inside, the former solar entrepreneur turned sustainable investor, Jigar Shah, is trying to use his perch overseeing the department’s Loan Programs Office to help move the multi-headed behemoth that is the U.S. electricity industry into a decarbonized future.

The Energy Department’s building looks and feels as daunting as that challenge.

To hear Shah tell it, successfully navigating this monumental task requires a major shift in how decisions are made by some of the biggest players throughout the energy sector. Evolving decision-making processes is a relatively mushy, amorphous goal compared with, say, installing a new generation of electricity wires — but in coming years, the latter will likely depend on the former.

Shah’s department provides loans and loan guarantees to help deploy large-scale and innovative clean energy technologies, ranging from renewable energy to carbon capture and storage. Sitting in his office earlier this month, I asked Shah why old transmission lines aren’t being replaced by advanced, more efficient wires (which I recently wrote about here).

“Culture and norms,” Shah told me. Faced with a new technology or innovation, a utility or regulator might respond that they don’t think a new technology is proven or dependable enough, Shah said. But sometimes pushback may be due to a lack of a familiarity with what’s new, he said, eliciting a vague and conservative response from a utility or regulator, like: “‘It’s just not something that our grid operators like to do.’”

The James V. Forrestal Building, where the U.S. Energy Department is located, is an intimidating structure. Photo credit: traveler1116 via iStock.

Replacing old transmission wires with newer conductor wires is largely seen as beneficial for an industry facing rising electricity demand for the first time in decades and for a country that struggles to build new transmission infrastructure. I pushed Shah: Given this urgent backdrop, why aren’t those cultural norms changing faster?

“Because we’re not focused on fixing them,” Shah said. “For a long time, many of the conversations that we’ve been having have been technology-focused.”

Thinking about new technological developments is exciting, Shah said. But he emphasized decarbonizing the power sector can’t be achieved with technological breakthroughs alone. It also requires focusing on what he calls “change management,” or evolving industry standards and processes to keep pace with necessary technical evolutions. Change management was also highlighted in a report the Energy Department published about grid enhancing technologies on April 16.

Decision makers are often rewarded for operating defensively, accustomed to thinking if they deploy a new technology and it doesn’t work “perfectly” they could face consequences, Shah said. Ergo, the status quo marches on.

“We’ve got to figure out how to give people protection so that they can do the right thing,” Shah told me. One way the Energy Department can do that is by providing validation and case studies giving utilities and regulators confidence a new technology works, he said.

The Edison Electric Institute, a Washington-based trade association representing power delivered to 75% of the U.S. population, said regulators are often driving the behavior of utilities.

“Every capital investment we make has to be approved by a state regulator,” Emily Fisher, the executive vice president of clean energy and general counsel at EEI, told Cipher. Each state has its own regulatory commission that all move at different speeds in permitting new technologies: “This is an ecosystem that has a lot of actors in it.”

Shah is not alone in his view.

“Getting a utility to try something new is a lot like getting a six-year-old to try a new vegetable,” said Abe Silverman, a lawyer who worked at the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities and is now researching energy issues at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

Regulators for those utilities “have primarily been economic regulators for the last 100 years,” Silverman told Cipher. “Suddenly, many state legislators and governors are tasking these organizations with leading the clean energy transition,” and that’s going to take time, political leadership and funding, Silverman said.

Indeed, the transition depends on a lot of utilities trying a lot of new vegetables.

Currently, financial incentives in the utility sector encourage companies to invest in new infrastructure instead of lower-cost improvements, Rob Gramlich, president of the electricity policy shop Grid Strategies, told Cipher. “Grid-enhancing technologies should help them and their regulators achieve reliability and affordability by delivering more [energy] over existing wires. But since they are low-cost, there is a profit disincentive in standard cost-of-service regulation,” he said.

Many utilities are “actively” working on getting up to speed on these new technologies, Fisher of EEI said. “A lot of these technologies are relatively new, and we have an obligation to run a reliable system. And so sometimes it does take a minute for us to understand how these technologies work,” she told Cipher.

Some utilities see adopting new technologies as an opportunity.

“As stewards of the electrical grid for customers and communities, utilities have a once-in-a-century opportunity to lead grid modernization,” Alexina Jackson, vice president of strategic development at the AES Corporation, an EEI member that owns both a utility and a renewable energy developer.

Silverman agreed regulatory reforms can help utilities eat their vegetables by requiring them to consider new technologies and changing their financial incentives. “Both options require that we rethink the utility-regulator relationship. But it can be done,” he said.

Such topics are likely to be on the docket in a May 13 meeting on transmission hosted by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), an independent federal agency that regulates the power sector. In a November 2023 letter, which FERC directed Cipher to when reached for comment on this story, FERC Chairman Willie Phillips expressed support for “advanced transmission technologies,” because “they often provide customers with the best bang for the buck.”

Back at the Energy Department’s headquarters, Shah said the agency can act as a validator for entrepreneurs and innovators. “When we evaluate the technology, then I think there’s a lot more credibility.”

In some cases, Shah’s office acts as an information matchmaker, using a utility serving mountain west states as an example. “We can say, ‘Well, here’s what Rocky Mountain Power is doing and they figured it out. How about I put you in touch with their experts and your experts and you guys share best practices?’” Shah said.

To Shah, it comes down to getting the behemoth power sector to operate in new ways.

“We just need to spend a lot more brain power on this culture and norms change management piece,” Shah said, “while we still do the innovation work that DOE has been amazing at for 45 years.”

Q&A with Shah

The rest of our conversation popcorned all over the energy transition landscape. Questions have been paraphrased and answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.

Q: What are your top line thoughts on how we should and should not be using hydrogen?

JS: We already use 10 million metric tons of hydrogen a year in this country. Decarbonizing that 10 million metric tons is a good use of clean hydrogen. Because clearly those processes, whether it’s ammonia or desulfurization of fuels or other things, require the use of hydrogen. So, those things, we should figure out how to decarbonize. That’s the first piece.

The next piece, though, is harder to answer. I think you’re not going to see this expansion of hydrogen for decarbonizing other industries like vehicle transportation, steel production, industrial uses, etcetera until we can get the technology to a point where you get the cost down.

Q: Your most recent monthly application activity report has a lot of loans requested for virtual power plants (networks of decentralized, smaller-scale energy producing and storage devices that can collectively respond to ebbs and flows in demand for electricity). What does that mean? What are those loans for?

JS: When you think about how the grid operates broadly, most of the cost of the grid comes from peak demand. As opposed to airline seats, where folks can kick people off a flight if they oversell it, we can’t take anybody off of the grid. If people need power for life-sustaining work or whatever it is, we have to provide it.

Electricity demand peaks are what cause the most cost increases in the grid. And we have a lot of tools to deal with peaks, but the number one tool is virtual power plants — making sure everything isn’t on at the same time if it doesn’t need to be. Things like water heaters don’t all have to be on at the exact same time after everyone finishes taking a shower in the morning.

We don’t tell people what we want to fund per se. They come up with ideas and come to us. You have a lot of folks who have traditionally been in thermostats figuring out how to navigate smart thermostats to provide some of this peak load management. We also have folks who are very active in electric vehicle charging looking to use batteries and micro-grids that can charge cars and also provide services to the grid.

Photo credit: S&P Global’s CERAWeek conference in Houston. Jigar Shah, the director of the Loan Programs Office, seen here speaking in Houston at S&P Global’s annual energy conference, CERAWeek.

Q: A new report from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory finds there are 2.6 terawatts of power generation and storage looking to eventually be connected to the grid. How does this fact impact the way you think about how you finance transmission projects?

JS: I think there is some translation required. Of the 2.6 terawatts there, about 14% of it is actually ready to go. A lot of the rest of those projects are in the planning phases and have put their application in so they can get an estimate of the costs of connecting to the grid.

We can unlock a lot of the latent capacity we have already paid for in our grid that we have invented here and frankly have been commercialized in the United Kingdom and other places. This is the work you have already written about — the dynamic line rating, the smart wires, the topology upgrades, etcetera. There’s a pathway forward, which should give people hope.

Q: What are you seeing in terms of the demand for pipelines for carbon dioxide and hydrogen? Is the lack of pipelines a barrier for the loan applications the LPO sees?

JS: Pipelines are easier than transmission lines because they’re normally underground. There are certainly political issues there. You’ve seen a lot of the negativity around the pipelines in Iowa. But CO2 is a straightforward thing. People know how to transport CO2; we know how to do pipelines safely.

Hydrogen is uniquely hard. Hydrogen is a very small molecule. If you run it through existing natural gas pipelines or existing pipelines, it would just leak out. There’s a lot of technology work being done at DOE on how we upgrade compressors, upgrade materials, upgrade things to be able to transport hydrogen.

Today, I’d say a lot of the hydrogen we’re looking at in the Loan Programs Office is being used at the place in which it’s being produced. It isn’t being transported anywhere, maybe 1,000 feet, but not miles. I think you’re going to see a lot more of that right now, just because it’s the safer way to do things today, while the rest of DOE is helping with getting the technology to the point where you can transport hydrogen in a low-cost way.

Q: I read you have a coffee mug that has “deploy, deploy, deploy” written on the side.

JS: It was a gift from a friend. There are so many technologies that are actually already demonstrated that we now can commercialize and get across the bridge to bankability; I’m purely focused on that. It’s not that I don’t think the rest of the concepts could be successful. It’s just not my specific job.