Surging power demand spurs smarter electric grid use

Explainers

Demand for electricity is shooting up in the United States following two decades of relatively flat electricity use — and yet building more transmission lines to bring new sources of energy online is a slow, bureaucratic process.

This tension is pushing the power sector to rethink how it builds and uses the power grid itself, which is actually a hodgepodge collection of several different grids that serve different portions of the U.S.

The urgency of the issue is mounting. Grid planners project 4.7% electricity growth in the next five years, almost double the growth projected just a year ago, according to a December report from the consulting shop Grid Strategies, which tracks projections grid planners file to federal regulators. That’s also likely an underestimate as more data centers, manufacturing and electrification efforts are set to push demand even higher in coming years, Rob Gramlich, president of Grid Strategies, told Cipher.

Transmission lines — the hanging wires that for many blend into the background blur of our day-to-day lives — are mission critical to the energy transition. The existing grid infrastructure was built to accommodate a continuous supply of energy from, largely, fossil fuel power plants. Bringing more clean energy online to replace fossil fuel plants will mean rethinking that setup. Wind and solar don’t generate energy all the time and the locations where those resources are the most intense are often far from population centers.

To be sure, the U.S. needs to figure out a way to build more transmission lines. Reaching net zero emissions will require increasing the country’s transmission capacity by 50%, according to a 2023 Princeton University report. And a number of technical and operational improvements could help get more out of the existing grid today.

Doing so will have real impact on local economies because data centers and manufacturers are forced to build where they can get power. “Grid capacity is the new gold,” said Hudson Gilmer, the CEO of LineVision, a company that makes a technology enabling power generators to put more power through the same wires. “It’s really the scarce resource that is going to determine where economic development and jobs happen.”

Let’s dive into three potential improvements: Optimizing the grid, making power lines more efficient and leaning into flexibility.

First improvement: grid enhancing technologies, called “GETs,” combine hardware and software systems to enable utilities to adjust, reroute and track the amount of electricity flowing through power lines in real time. Without such insights, utility companies make ultra-conservative estimates about how much electricity can go through a wire to prevent it from overheating and sagging.

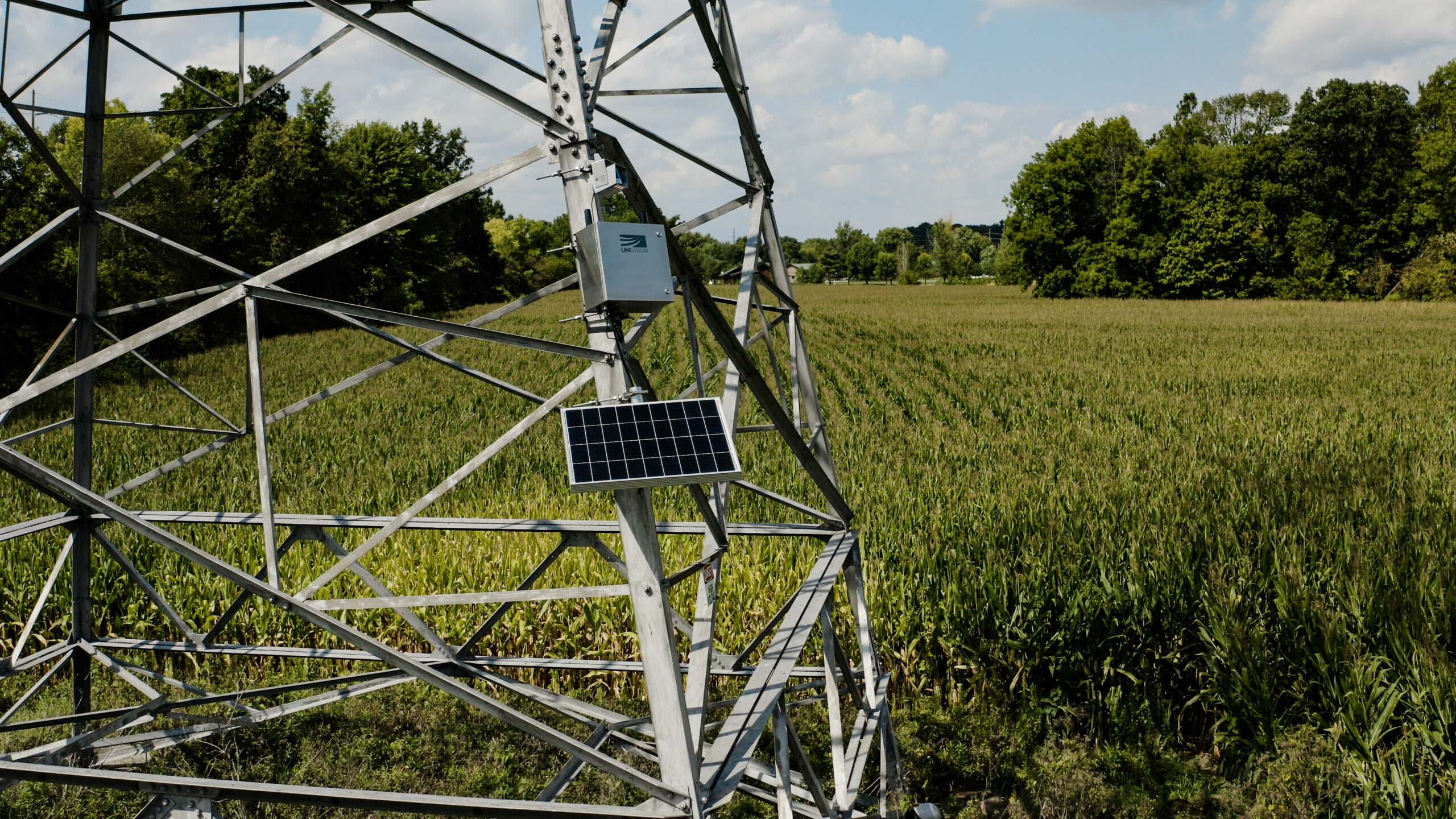

Boston-based LineVision installs sensors on electrical towers and poles to provide real-time information about the current conditions around each line. LineVision has grown rapidly since 2018, with its revenues increasing every year 50 to 100%, according to Gilmer.

LineVision’s sensor can be seen installed on an electric power pole in Indiana. Photo credit: LineVision.

“Even a little bit of wind cools the line enough that you can safely put much more power through that line,” Gilmer told Cipher on the sidelines of the CERAWeek energy industry conference in Houston in March.

The sensors use pulsed lasers to measure the exact location of the wires and how much they’re sagging to determine how hot the wires are at a given moment. LineVision also tracks forecasted temperature and wind speeds to predict weather conditions to provide a real-time estimate for how much electricity can safely go through the wires at that moment.

“We see up to a 40% increase in average capacity on a line,” Gilmer told Cipher. And installing the sensors “can be done in a matter of two or three months,” he said, which, in transmission-line timescales, is the blink of an eye. LineVision counts leading utilities including The AES Corporation, Avangrid, National Grid and Xcel as customers.

For utilities and regional transmission organizations, non-profits that operate most of the power systems in the U.S., “GETs should be a top priority. Deploying GETs on the existing grid will be like adding a lane on the highway system,” Julia Selker, executive director of the advocacy group Working for Advanced Transmission Technologies Coalition, told Cipher.

Installing GETs would allow twice as much wind and solar generation to come out of the interconnection queues (grid terminology for a waiting line) with only “minimal transmission upgrades” and save approximately $20 billion nationwide or, indirectly, $60 per person per year, said Selker. GETs would also allow transmission lines to carry larger loads, thereby limiting the need to replace or rebuild certain lines, she said.

Second improvement: reconductoring is a wonky word for a simple, idea — replacing existing wires with better, newly developed wires that can transmit more electricity.

By replacing conventional wires with advanced conducting lines made of ultra-pure aluminum wrapped around a carbon fiber core, the company TS Conductor “can triple the transmission capacity” of a conventional electrical line, Jason Huang, the CEO of TS Conductor, told Cipher. Investors in TS Conductor include Next Era, National Grid and Breakthrough Energy Ventures (which also supports Cipher).

Montana-Dakota Utilities did a reconductoring project in February 2021 near Bismark, North Dakota, where it replaced conventional wires with the advanced conducting wires made by TS Conductor. Photo credit: Montana-Dakota Utilities.

The company built its first manufacturing facility in 2022 and became profitable in 2023, Huang said.

The Montana-Dakota Utilities Company used TS Conductor’s advanced wires to upgrade a 12-mile line on the outskirts of Bismark, North Dakota, in February 2021 so it could handle the increased load from a new wind farm. Initially, the utility thought the project would involve swapping most of the poles along the line with taller ones to keep the wires sufficiently off the ground, Jon Wahlgren, senior engineer at Montana-Dakota Utilities, told Cipher.

“By using the TS Conductor, we were able to achieve the same electrical capacity by just replacing the conductor, and none of the structures,” Wahlgren told Cipher, saving two years and 40% of the cost.

Another company in the space, Veir, is developing wires capable of carrying five to 10 times more electricity than a conventional conductor, CEO Tim Heidel told Cipher. To make its wires, Veir uses a high-temperature, superconductive tape that includes a thin layer of rare earth barium copper oxide surrounded by other materials to provide flexibility, durability and the ability to stay cold.

“Our novelty, and really, the core of our technology, is a new approach to cooling these lines,” Heidel told Cipher.

The company is currently testing its lines in a pilot phase and hopes to have its first commercial-scale project operational in about three years. The lines will be more expensive, particularly early on, than conventional wires. But the new lines may still be able to compete economically on projects slowed down by permitting or siting challenges. “Against those, we believe we can be at cost parity or even below — even on day one,” Heidel said.

Principal engineer at Veir, Dawood Aized, shows Massachussettes Congresswoman Katherine Clark the heat exchange unit that will sit on top of a transmission pole at Veir’s headquarters in Woburn, Massachusetts, in 2022. Photo credit: Veir.

Third improvement: utilities and customers need to embrace adding more flexibility to grid operations.

“The transmission grid is never utilized at more than 50% of capacity because the whole grid you’re seeing is built for the peak,” Andrés Gluski, CEO of the global renewable developer The AES Corporation, told Cipher on the sidelines of CERAWeek. “But the peak is never 24 hours a day.”

Getting more from the grid than we already have requires capitalizing on currently unused hours of transmission capacity. “Think about it. It’s kind of like you have all these beach apartments” sitting unoccupied most of the year, Gluski said. “You could do the Airbnb of transmission.” Saving electricity generated from wind and solar in batteries by sending it through transmission wires when those wires are otherwise not being used to their maximum capacity is akin to renting out your beach apartment when you’re not using it.

Energy demand only peaks and maxes out transmission lines for 1 to 6% of the entire year, according to numbers shared by Ian Blakely, chief technology officer at Enchanted Rock, a company that manages reliable backup power for commercial, industrial and institutional customers. For the rest of the year, the grid has plenty of headroom.

The network operations center at the Enchanted Rock headquarters in Houston. Operators watch for power outages and monitor backup power generators for customers like Walmart, Buc-ee’s and H-E-B. Photo credit: Cat Clifford.

The inflexibility of our current management of the grid is making it harder for new infrastructure like data centers to come online.

Historically, a data center might shop utilities for the cheapest power and they might expect to get connected to the grid in one to two years, said Blakely. “Now, what’s happening in a lot of places is, they’re being told, ‘Well, actually, it’s going to take three, four, five, six, seven, eight — 10 years,’” Blakely told Cipher in Houston. “And in some places, they’re basically being told, ‘No, we can’t serve that load.’”

Electricity-intensive customers that are more flexible and can allow a utility to shut their power off when the grid gets constrained will likely come online faster than customers unwilling to make such concessions, Blakely says.

Utilities and regulators also need to solve for “a business model problem,” says Gluski. Companies that build transmission lines are disincentivized to invest in low-hanging fruit solutions, like GETs.

“Often transmission companies make more by investing more,” Gluski said. “If you say you can do it with a third of the money, you make a third of the profits.”

One possible solution is to shift to a “shared savings incentive” business model whereby regulators allow utilities to earn a portion of the anticipated savings their infrastructure investment would net for the system, Selker told Cipher. “Changing the utility incentives would catalyze GETs adoption across the country.”

Editor’s note: TS Conductor’s and Veir’s investors include Breakthrough Energy Ventures, a program of Breakthrough Energy, which also supports Cipher.