Wind Blows Favorably on Japan’s North Island

Latest News

ISHIKARI, Japan — Japanese history recounts how strong typhoon winds twice saved this island nation from Mongol invaders seven centuries ago.

Wind may now once again help rescue Japan, this time from an overweening dependence on fossil fuels by harvesting electric power from the reliably steady gusts over the Sea of Japan.

Tatsuyuki Kato, mayor of the city of Ishikari in the northern region of Hokkaido, is a big advocate of wind power, not only to address climate change but also to boost the local economy. His coastal municipality, like many Japanese cities, struggles with the threat of a declining and rapidly aging population.

“We want to contribute to addressing a major challenge for the world,” he told Cipher during a recent visit to Ishikari, which functions as the port for Hokkaido’s largest population center, Sapporo, 30 minutes away by car. “At the same time, this will help grow our population, boost business activity and create jobs and tax revenues.”

The city, and broader region, could soon be at the center of Japan’s wind ambitions. Ishikari’s first offshore wind project, a 112-megawatt installation, is expected to be operational by the end of this year. By 2040, Hokkaido could host as much as one-third of Japan’s wind power, the most of any region in the country. Parts for the turbines could be seen lined up in the port for assembly during Cipher’s visit.

Japan is heavily reliant on fossil fuels, almost all of which must be imported since the country has few coal, oil or natural gas resources of its own. The dependence deepened in 2011, when a nuclear disaster forced the shutdown of nearly all of the country’s reactors. They generated nearly a third of Japan’s power. Today, most remain idle.

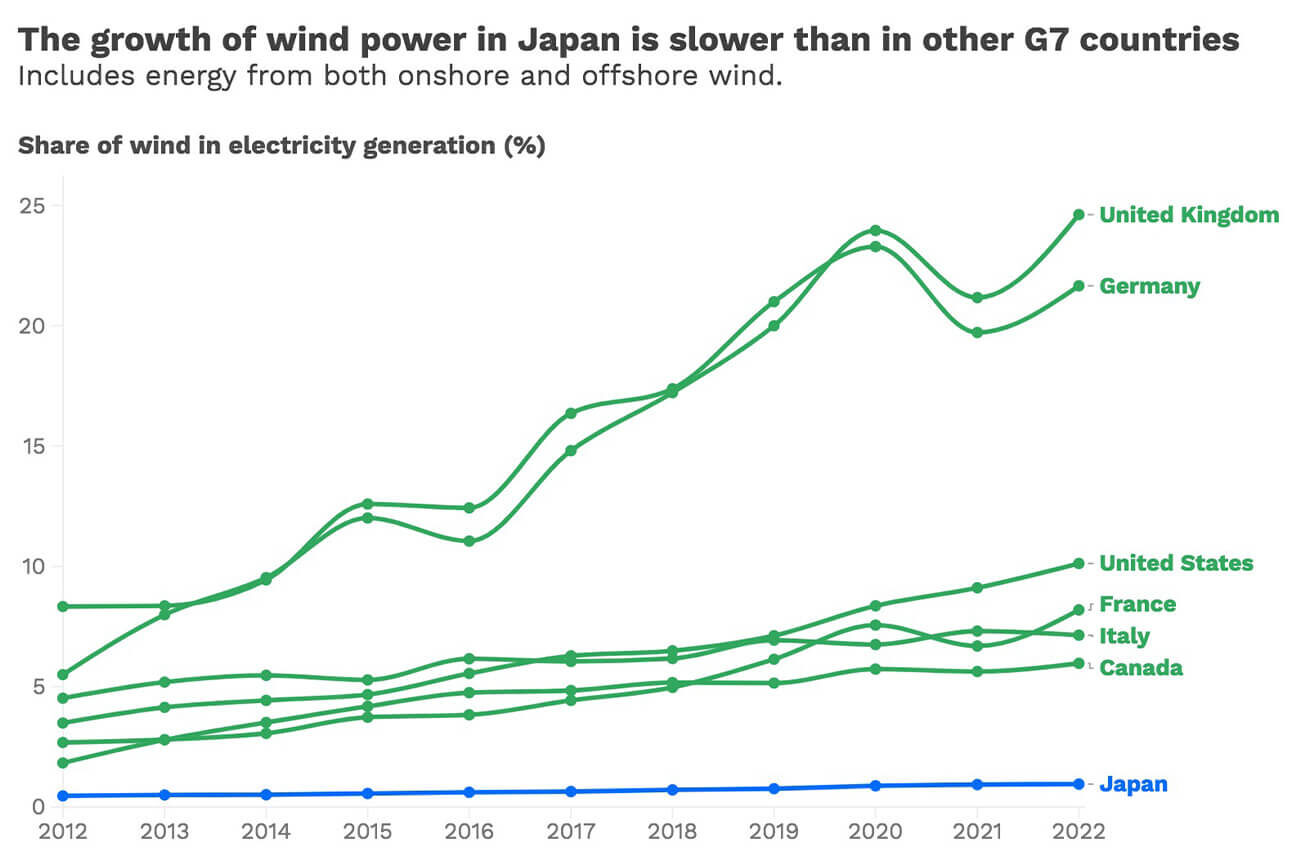

To fill the gap, Japan turned to liquified natural gas and ramped up solar power installations. More recently, the government has targeted wind power, particularly offshore, for significant growth, aiming to become a global player in the burgeoning industry.

If Japan’s wind ambitions work out financially and continue to grow, they could give a major boost to the global offshore wind industry, which has slumped recently as costs rise.

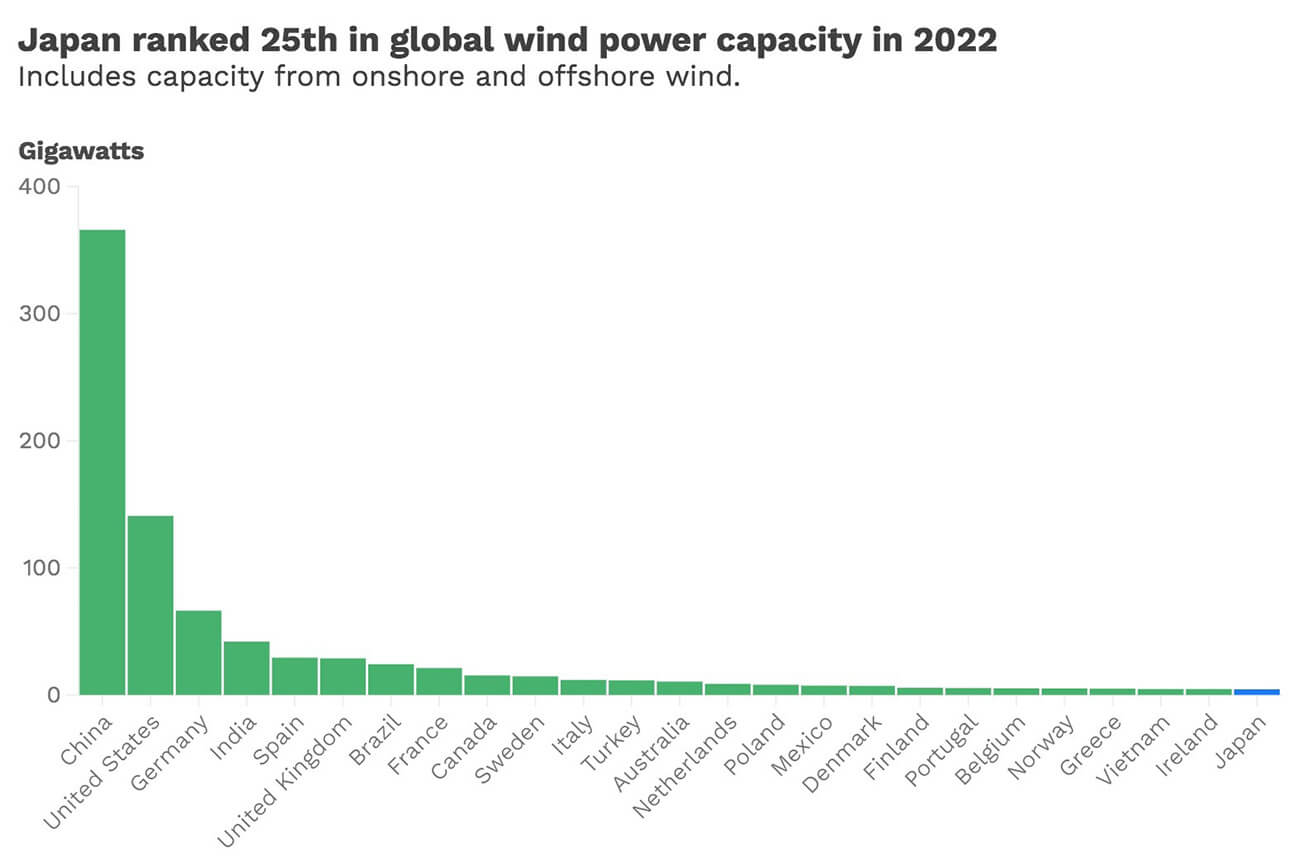

Japan plans to authorize 10 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2030 and have about 5.7 gigawatts of it up and running by that year. That would build on its existing 4.6 gigawatts of mostly onshore wind capacity. Just 10 years later, in 2040, the country hopes to have as much as 45 gigawatts of mostly offshore wind, triple its 2030 goal.

Renewable energy advocates are pushing for dramatically more. They argue 31 gigawatts of wind power could be installed by 2030, almost 60 gigawatts by 2035 and 180 gigawatts by 2050, when Japan has committed to achieving net zero emissions.

Source: Ember

Projects on Japan’s main island to the south are leading the offshore wind surge, with the country’s first large-scale commercial operations starting this year along the western coast, totaling 139 megawatts. Auctions held over the past several years could usher in another 3.5 gigawatts.

Those are small numbers compared to the 14 gigawatts of offshore wind built by the United Kingdom and the 31 gigawatts built by China (though still more than the 42 megawatts currently operating offshore in the United States).

Hokkaido will be at the center of the country’s efforts. The sprawling, lightly populated region contains almost half the country’s wind energy potential and accounts for just a fraction of the country’s energy demand. Meaning there’s room to grow clean-energy hungry industries nearby while also feeding power to densely populated cities further south.

Ishikari mayor Kato says the wind industry will benefit the municipality’s 60,000 residents in part by attracting jobs in other sectors. His administration is targeting data centers, which increasingly covet clean energy to meet their own decarbonization targets as well as the region’s cool climate to reduce electricity consumption needed for air conditioning. Kyocera Corp., an electronics company, has a data center in the city and plans to expand thanks to the new supply of clean energy.

The mayor hopes the wind project currently under construction, which will be the country’s largest combined wind and power storage facility, and others expected to be built along the blustery coastline, will spawn local construction jobs and an ongoing network of local maintenance companies that attract and employ residents.

Longer term, Hokkaido officials and the central government have an even grander plan to use the region’s green energy potential to attract computer semiconductor manufacturers.

The plan received a boost last year when a consortium of Japanese corporate heavyweights, including Toyota Motor Corp. and Sony Group, announced a joint venture with IBM Corp. that will spend $36 billion (about 5 trillion yen) to build an advanced semiconductor plant in Hokkaido.

Despite these lofty plans, wind power remains controversial in the environmentally conscious region, and the estimated $31 billion (about 4.5 trillion yen) cost of building new transmission and interconnections to Japan’s main island is daunting.

“I’m working hard to persuade the people of Hokkaido that renewable energy projects here are beneficial not only to far away populations but also to our local community and economy,” said Nobuhiro Komoto, an official from the resources and energy section of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry who is working with the Hokkaido government on clean energy strategy.

At least one onshore wind project has been canceled amid cost increases and local opposition near Ishikari. Some residents worry about the environmental and economic impact of wind power, especially on the critical fishing industry. Some residents are wary because Hokkaido, once the coal producing region of Japan, has experience absorbing the environmental cost of producing energy largely for the benefit of cities to the south.

“Most of the electricity will go to Tokyo,” said Chikira Makoto, an Ishikari resident who is part of a community group opposed to the rapid expansion of wind power in the area.

Unlike much of Japan, Hokkaido has a history of wind power, albeit on a smaller scale. Toru Suzuki was a truck driver delivering groceries for a local food cooperative after the Chernobyl nuclear plant disaster in 1986, when it struck him that the energy sector needed a safe, locally based means of providing electricity.

He eventually started the Hokkaido Green Fund and has pioneered a model of community residents pooling funds and investing in wind projects. With another boost after the Fukushima nuclear disaster, the fund has helped build dozens of wind projects across the country, most of them with deep local ties, right down to having local school children choose names for turbines.

As wind power in Japan grows to a vastly larger scale dominated by bigger and more expensive offshore turbines, government and industry officials need to ensure local residents still benefit tangibly to build support in Japan’s consensus-minded society. That’s the biggest lesson he’s learned.

“The community needs to get the benefits and that creates a virtuous cycle,” he says.