Looking back to move ahead: Lessons learned from cleantech 1.0

Harder Line

Conventional wisdom says cleantech 1.0 was a bust.

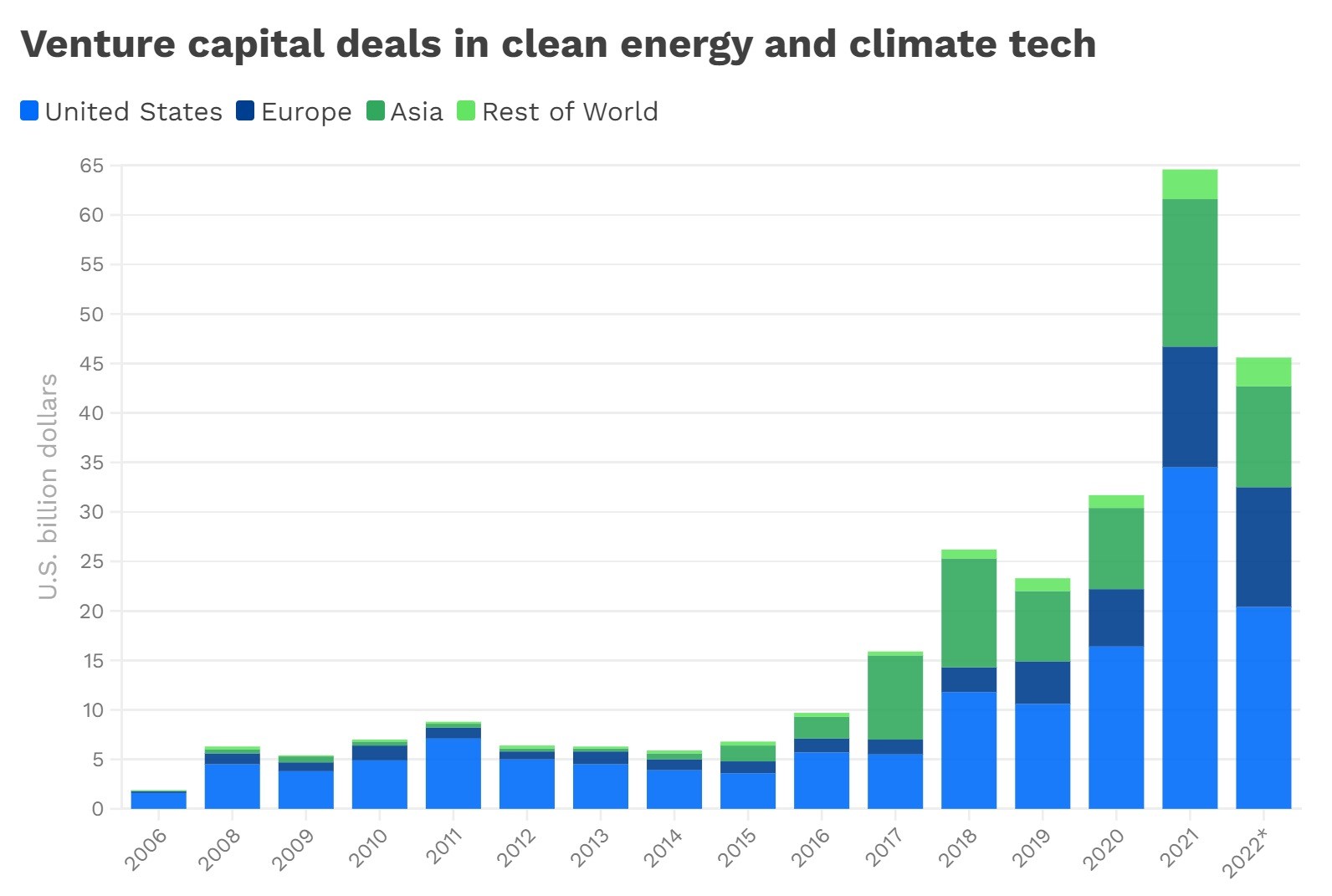

In a nutshell, cleantech 1.0: Beginning in 2006, venture capitalists poured more than $25 billion into clean energy technologies. Over the next five years they would go on to lose over half that, led by losses in biofuel and solar startups (remember Solyndra?).

That sounds like a bust. But closer examination reveals successes amid losses and lessons learned that will help ensure today’s far larger climate tech investments don’t face similar fates.

“Cleantech 1.0, properly done, wasn’t a bust,” said Vinod Khosla, founder of Khosla Ventures, in conversation with fellow prominent venture capitalist, John Doerr, chairman of Kleiner Perkins, at the Breakthrough Energy Summit in Seattle Tuesday.

I looked at the returns. We turned $1 billion, through a lot of losses, into $3 billion of value. So, a surprising number there.

Successful investments of Kleiner Perkins during Cleantech 1.0 include smart thermostat firm Nest, which Google acquired in 2014, and Enphase, a solar energy company that went public in 2012, according to Doerr’s office.

$3 billion off $1 billion is considered a decent return for a fund writ large, but returns haven’t come as fast as they traditionally have for funds more focused on software companies.

Khosla mentioned several companies his firm invested in that remain operating today, including electric-vehicle battery maker QuantumScape and carbon recycling firm LanzaTech.

“They took a lot more patience and nurturing,” Khosla said.

Some technologies probably still need more time, judging by QuantumScape’s stock. It’s been on a gradual decline ever since a blockbuster opening day in 2020 (granted, the overall stock market has been dismal lately.)

Both Khosla and Doerr faced headline-grabbing losses in cleantech 1.0.

Khosla invested in KiOR, an advanced biofuels startup that went through high-profile bankruptcy in 2014.

As for Doerr, forget horses, he bet on the wrong car back in circa 2007. His firm invested in Fisker, a now little-known electric vehicle company, over Tesla.

“It’s a very painful mistake,” Doerr said.

His thinking was rooted in the fact Fisker was led by known automotive leaders, whereas Tesla wasn’t. That type of thinking may not hold for technologies that upend the status quo.

“I can’t think of one large example [of change] driven by somebody who knows the space super well,” Khosla said. “[I] much prefer people who think of first principles and hire the experience around them to surface the problems that might come up.”

At a macro level, investments in Cleantech 1.0 dried up because of two factors: the 2008 economic recession and the onset of the U.S. oil and natural gas boom, which dropped fossil fuel prices and made more expensive clean energy even less financially attractive.

Climate urgency kept growing, and in 2015, world leaders agreed to the Paris Climate Agreement, where virtually the entire world agreed to limit greenhouse gas emissions. So began another cleantech investment opportunity.

Fast forward to today. The cleantech 1.0 boom seems more like a whimper. Venture capitalists have invested more than $224 billion in climate tech between 2015 and Oct. 18 of this year.

Source: PitchBook• Data compiled upon request from Cipher. 2022 data complete through Oct. 18.

“I don’t think there is any dispute that the original cleantech 1.0 got us to where we are now,” said Molly Wood, a climate tech investor at the VC firm Launch.

Although comparing the two might seem unfair considering the mountains of money being invested today, the molehill of yesteryear offers lessons.

“Costs are king in climate,” Doerr said. “People will not pay a premium for an equivalent green product.”

Some of these lessons are being heeded.

Two VC firms launched after the Paris Climate Agreement, including Breakthrough Energy Ventures, whose board includes Khosla and Doerr, and The Engine built by MIT, are focused on technologies that will likely take longer to develop, so they’re intentionally allowing for more than the typical three to five years for returns.

“Climate tech as a sector is beginning to benefit from a more developed investment stack, akin to what software and biotech startups have had for decades,” said Katie Rae, CEO & managing partner of The Engine. “These are signs that point to venture scale returns and the possibility of very large companies.”

Awareness of climate change among the public, governments, corporations and investors is greater than it was during cleantech 1.0. Several factors are driving this, including the impacts of climate change being felt by more people and renewable energy costs are plummeting.

The enactment over the past year of major U.S. climate laws, led by the nearly $400 billion in government incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act, is also boosting climate tech companies.

“I don’t see us transitioning to the new clean energy economy without enabling action [from government],” said Doerr, referring to a comment U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said in earlier session at the same conference.

Blind spots may await, especially with a global economy facing an energy crisis, inflation and persistent supply chain shocks.

“I worry about it a lot,” Khosla said. He said he’s advising climate tech startups to prepare for lower evaluations. “That’s a risk you should manage very tightly.”

Editor’s note: Breakthrough Energy Ventures (BEV) is a venture capital fund within the Breakthrough Energy network, which also supports Cipher. BEV is also among QuantumScape’s investors.