In Norway, global tension over fossil fuels and climate change

Harder Line

Oslo, Norway — This Nordic country is grappling with an inner conflict, accentuated by Russia’s war in Ukraine, that pits its oil and gas wealth against its climate change ambitions.

The struggle in Norway, one of the world’s wealthiest nations thanks to its plentiful supplies of oil and natural gas, is an acute illustration of the world’s omnipresent battle with itself: Our dependence on fossil fuels is ingrained into every aspect of the modern world, yet increasingly so is climate change, precisely because of those same fuels.

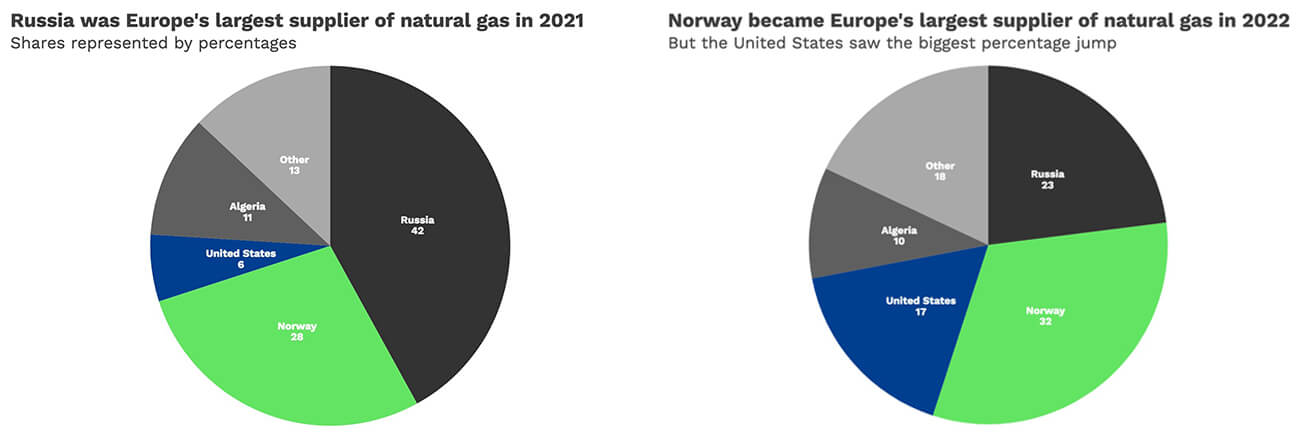

Norway is, on the one hand, saving Europe with its natural gas resources after Russia, historically the bloc’s largest supplier, abruptly turned off the tap. On the other, Norway is aiming to increase its oil and gas resources at a time scientists say the world must begin winding down all fossil fuel use and production.

“If Norway were to say, ‘well Europe is in a dire situation on gas, but we have decided, as our contribution to climate change mitigation, to cut down,’ that means more coal in Europe. So, that’s not the way to do it,” said Jonas Gahr Støre, the Norwegian prime minister, last week at the Oslo Energy Forum.

The Forum, a high-level gathering of about 200 people now in its 50th year and backed by Norwegian energy firms, has previously included mostly oil and natural gas executives. It was opened to the media for the first time this year and sought to foster a broader debate on the energy transition.

Due in part to Norway’s central role helping Europe weather its energy crisis, the forum drew big global names, including Amina Mohammed, second in command at the United Nations, and Bill Gates, founder of Breakthrough Energy and co-founder of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The event also included virtual messages from John Kerry, President Biden’s special envoy on climate change, and Simon Stiell, executive secretary of the U.N. Convention on Climate Change, which oversees the annual negotiations on the topic.

I visited Norway to help co-moderate the conference, so I had a front row seat to the country’s inner conflict. I accepted the invitation largely because of what the event reveals about our world’s broader climate debate.

The forum’s dialogue offered a glimpse into what is sure to be an intense U.N. climate conference, known as COP28, late this year hosted by the United Arab Emirates, another oil-producing nation that’s also a member of OPEC, the mostly Middle Eastern oil cartel.

“We will go to COP28 to perhaps have one of the most difficult discussions where fossil fuels will be upfront on the agenda,” Mohammed said at the forum. “How can we ensure that is a more robust and constructive discussion and not one that brings us into a head-on collision?”

I first visited Norway in 2018 to tour the government’s planned facilities to capture and store carbon dioxide emissions (CCS). Arguably more than any other nation, Norway has made CCS central to its climate plans. That’s because it’s one of the few technologies that can, if executed as envisioned, allow a society to tackle climate change while continuing activities that emit greenhouse gases.

Norway’s flagship project, called Longship, includes a carbon storage facility under the ocean floor off Norway’s coast and carbon capture equipment installed on a cement plant and waste incinerator in Oslo. Construction on the CCS equipment is underway at both plants with completion slated for 2024 and 2025, respectively.

The project costs the equivalent of $2.6 billion, with the government footing about two-thirds of that bill, according to Tove Dahl Mustad, director of benefits realization and market developments at Gassnova, the government-owned carbon capture company leading the project.

“Norwegian authorities and Norwegian industry have never before invested a larger sum in a single climate project,” Mustad said.

Norway also taxes its oil industry at a staggering 78%, imposed a national carbon tax decades ago and doesn’t allow flaring of methane, a potent greenhouse gas and the primary component of natural gas.

Its majority state-owned oil and gas company, Equinor, is forging ahead on offshore wind and clean hydrogen, two technologies whose competencies transfer well from petroleum expertise.

“Norway is such a Rorschach test for what you prioritize in the oil and gas industry,” said Andrew Logan, an oil and gas expert at the U.S.-based nonprofit group Ceres, which works with investors to be more sustainable. “It’s a clean operator, it has a carbon tax and is good on methane.”

But:

“On the other hand, they’re exploring in the Arctic. No one else is doing Arctic exploration except Russia,” Logan said. “They’re expanding the frontier of oil and gas production in a way that does seem short-sighted.”

The government approved 22 oil and gas drilling projects off the Norwegian Continental Shelf last year, most near the year’s end, according to Rystad Energy, a Norway-based energy consulting and research firm.

Within five years, Norway is on track to go from supplying 24% to more than 30% of all European gas, concluded Rystad Energy, a shocking increase for an industry that usually changes at a glacially slow pace.

Source: Rystad Energy data provided to Cipher • This analysis covers Europe’s import mix and includes the European Union and the United Kingdom. Other includes seven countries, largely Qatar and Nigeria.

Logan said Norway should at least have a plan to eventually wind down its oil and gas industry decades from now, like what California, another climate-leading and oil-producing region, has done. Støre rejected that notion, in response to my question on the matter.

“Fixing a date or deliberating doing that is the wrong approach,” Støre said at the forum. But Norway’s biggest customers are adamant they’re not in a long-term relationship with oil and gas.

“Today, we are very, very grateful that Norway has become the biggest provider of natural gas,” said Christian Maaß, who leads the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, in a virtual interview at the forum in Oslo. “And also, we’ve talked about the mid-term and the longer term. It’s crystal clear that Germany is moving away from fossil fuels.”

Norway is betting that in a future with vastly less oil and gas, it will be among the world’s last producers (I call that a crude game of musical chairs). Its petroleum-funded sovereign wealth fund, worth more than $1 trillion, gives it a better shot than most other oil-producing nations.

Støre said his country has a goal of reducing emissions from its oil and gas industry 50% by 2030 and acknowledged the industry will gradually decline (but not go away altogether) in the longer term.

“We have to be trustworthy in the sense that we can get the emissions down,” Støre said, “that the transition is real.”

Editor’s note: Breakthrough Energy, which Bill Gates founded, supports Cipher.