Clean tech is not reaching the developing world fast enough

Latest News

Not enough cash is flowing to clean energy technologies in the developing world, widening the investment gap between rich and poorer countries and hampering the energy transition.

How to boost clean technology deployment in lower income economies is front and center at this year’s COP27 climate negotiations in Egypt, which kicked off on Sunday. The question falls under one of the wider—and thorniest—themes at the talks: climate financing.

Amid growing frustration from developing countries, advanced economies are under pressure to boost their public and private contributions to help the rest of the world.

“Our ability to access electric cars, our ability to access batteries or photovoltaic panels are constrained by those countries that have the dominant presence and can produce for themselves, but the Global South remains at the mercy of the Global North on these issues,” Mia Mottley, the prime minister of Barbados, said Monday in an impassioned speech during the conference in Sharm el-Shiekh, Egypt.

Countries considered part of the Global South, or deemed developing, low-income or emerging markets are loosely defined. This group is generally considered most countries in Africa, many parts of Asia and Latin America, and several other parts of the world, including island nations like Barbados.

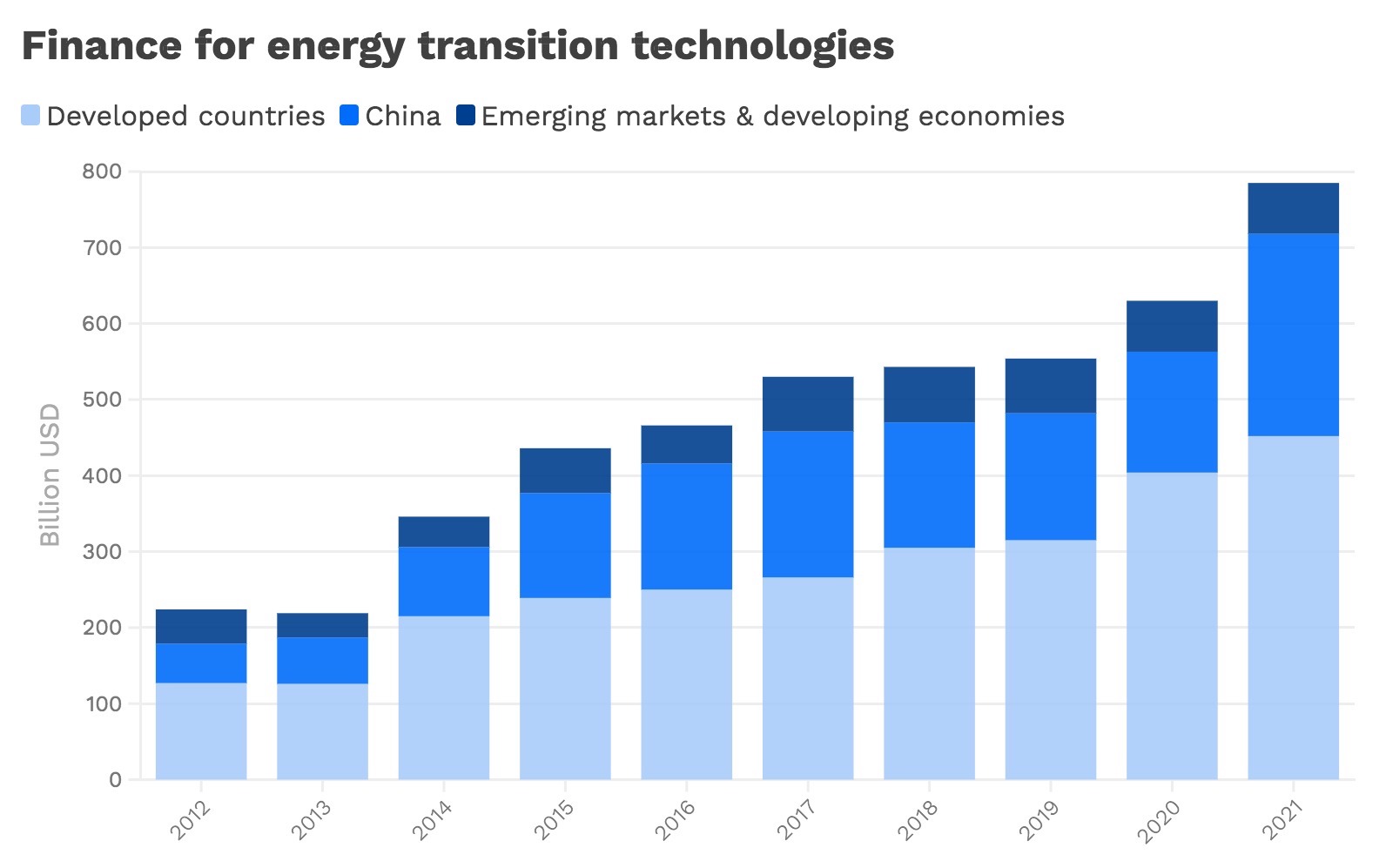

In 2021, global investments in low-carbon energy technologies hit a high of $785 billion, spiking 24% from the previous year. But the growth came almost entirely from richer nations, according to a report published this month by BloombergNEF.

Meanwhile, last year the share of financing for energy transition technologies going to emerging markets and developing economies stood at 8%, the lowest level in 10 years and far below the 20% peak in 2012, the report found.

Source: BloombergNEF • Emerging markets and developing economies includes most countries in South and Central America, Africa and Asia, excluding China, Japan and South Korea. Energy transition technologies include renewable energy, carbon capture and storage, electrified heat, electrified transport, energy storage, hydrogen and nuclear. Investment numbers include both equity and debt and refer to new and existing projects.

The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) recent World Energy Outlook also determined “virtually all of the global increase in spending on renewables, grids and storage since 2020” has taken place in advanced economies and China.

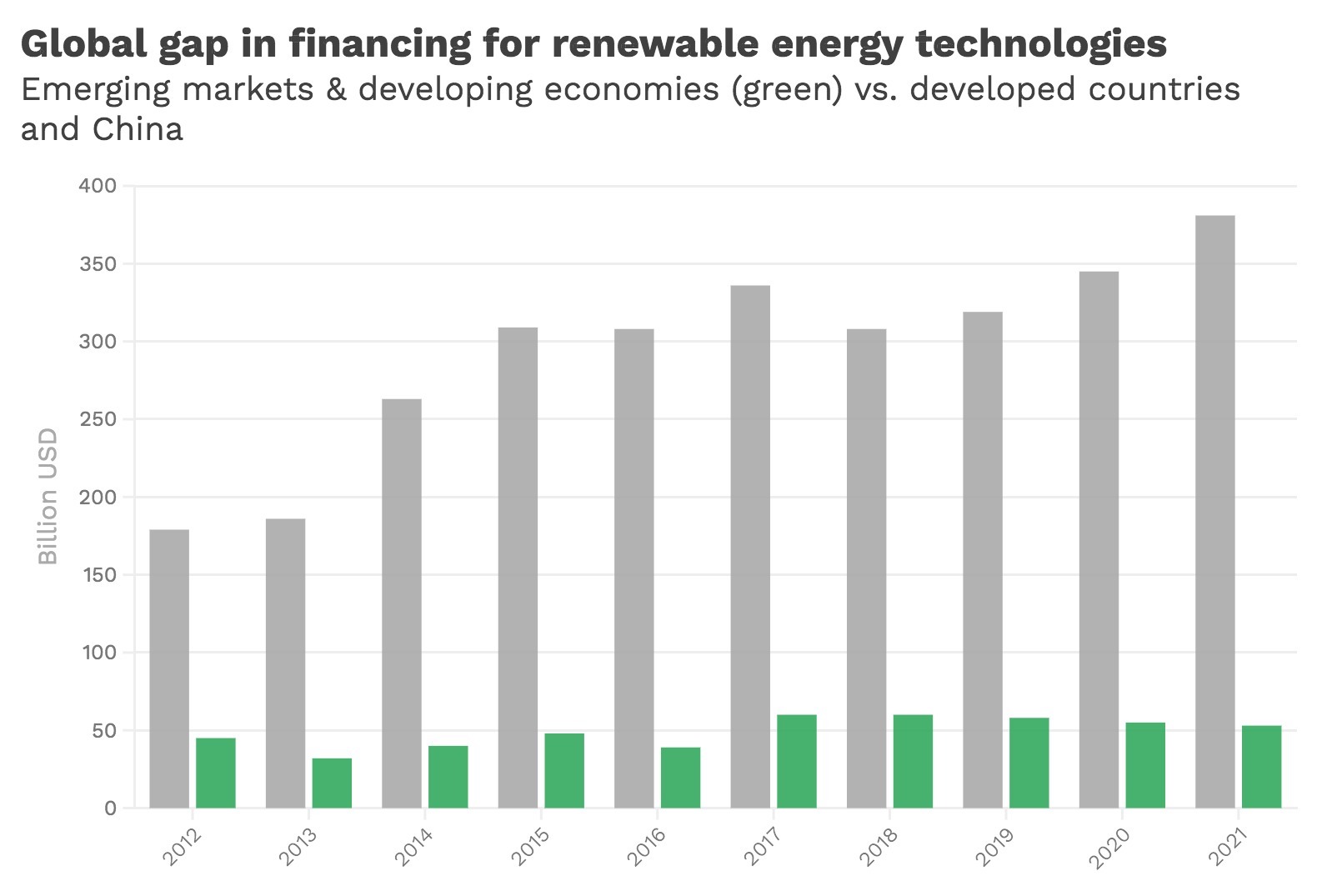

The amount invested in clean energy in emerging and developing economies, excluding China, has remained flat since the Paris Agreement was adopted in 2015, the IEA said. That’s a “worrying signal” because energy demand is on the rise in those regions, the report stated.

“The emerging world is actually getting starved of capital right now,” Larry Fink, the CEO of multinational investment firm BlackRock, said in October at the Breakthrough Energy Summit in Seattle.

The reasons are diverse yet interlinked. Borrowing rates and capital costs are higher due to (both perceived and real) risks to projects in developing countries, such as political instability and policy uncertainty.

Those costs, in turn, diminish private-sector appetite in the region. Many investment firms lack a solid presence on the ground to better judge the potential of a project, which deepens a cyclical dearth of financing.

Borrowing rates in advanced economies are between 1-4% but stand at 14% in the developing world, Mottley said.

“How many more countries must falter, particularly in a world that is now suffering the consequences of war and inflation and countries are therefore unable to meet the challenges of finding the necessary resources to finance their way to net zero?” Mottley asked in her COP27 speech in front of hundreds of other country leaders and delegates with a large projection of wind turbines and forests behind her.

What’s more, in a cruel irony, developing nations are also finding it increasingly difficult to afford to respond to extreme weather events made worse by global warming primarily caused by wealthier nations.

While renewables have become the cheapest form of electricity generation in the developed world, the cost of capital for a solar photovoltaic (PV) plant in 2021 in emerging economies was between 2-3 times higher than in advanced economies and China, according to the IEA report.

“The availability of technology has been dismal for developing countries,” Wael Aboulmagd, Egyptian ambassador and special representative to the COP27 president, said in a recent briefing with reporters. “The need to purchase is very restrictive because technologies are expensive.”

Many large-scale renewable energy projects in the developing world only make economic sense when assessed on a 20- to 30-year time horizon, according to a new report from the Rockefeller Foundation and Boston Consulting Group. But “finding long-term financing can be nearly impossible” for power companies in those regions due to political instability and project costs, the report found.

Building an unsubsidized solar plant in Ghana, for example, would cost about 140% more than building the same plant in the U.S., the report found.

Environmentalist and former U.S. Vice President Al Gore, who also spoke at COP27 on Monday, said Africa has 40% of the world’s renewable energy potential, yet a developer who wants to build a solar farm in Nigeria would have to pay interest rates seven times higher than in many high-income countries.

“That is unjust; it’s insane,” he said.

Source: BloombergNEF • Emerging markets and developing economies includes most countries in South and Central America, Africa and Asia, excluding China, Japan and South Korea. Renewable energy technologies include solar, wind, biofuels, biomass and waste, geothermal, marine, power transmission and small hydro. Investment figures refer to new and existing projects.

As part of its annual outlook briefing, IEA executive director Fatih Birol sent a blunt message to the group’s 31 government members, almost all of which are wealthier nations, ahead of the climate talks: “It’s time for advanced economies, so-called rich countries, to show that they are serious about climate change by providing support for clean energy investments in developing countries, especially Africa.”

The Egyptian ambassador, whose country is not an official member of IEA but a lower level “association” country, agrees.

“Until and unless we find a solution to the issue of technology,” Aboulmagd said, “countries will continue to struggle, to be reluctant and maybe not even prioritize spending their already stressed budget money on moving to renewables.”