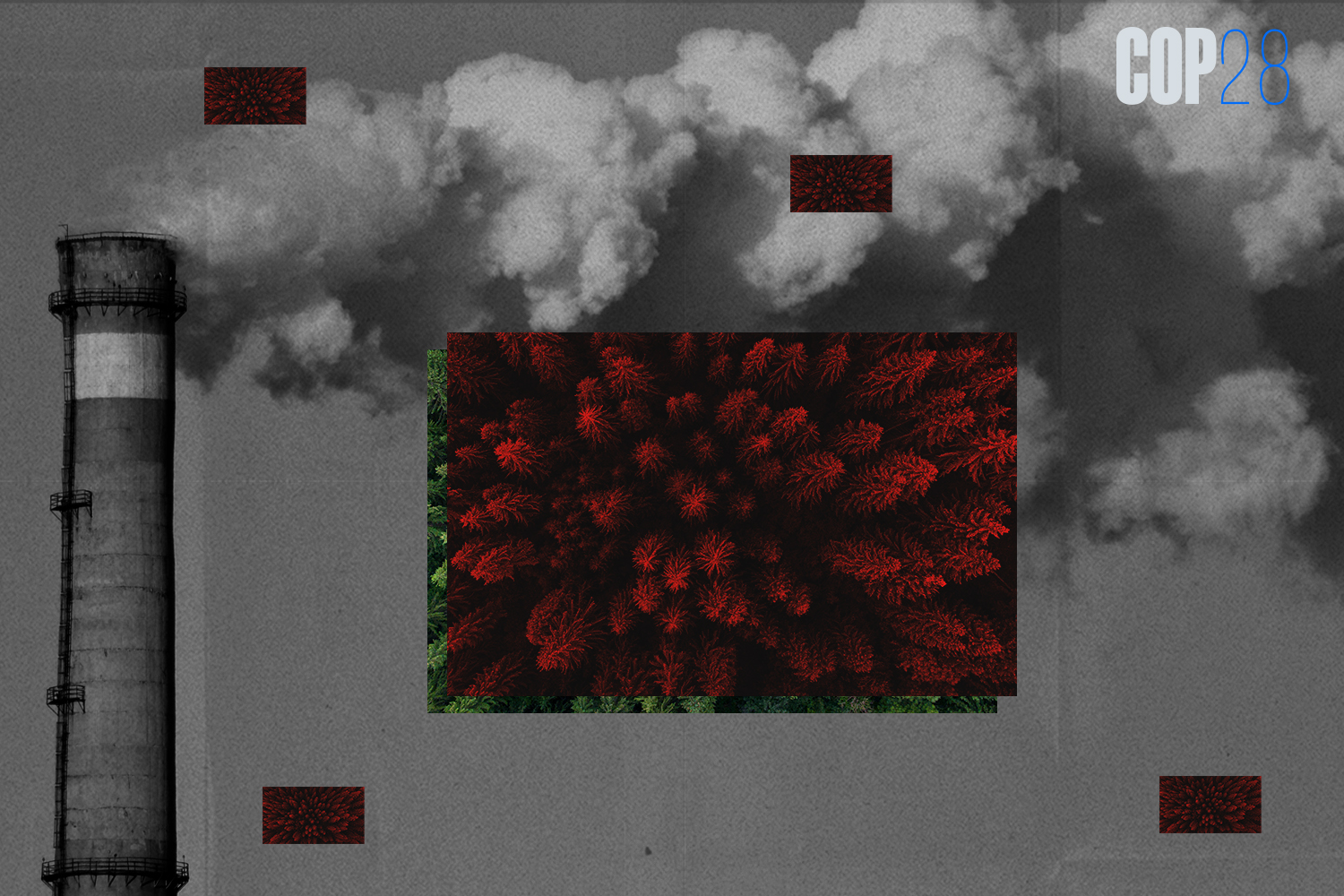

Carbon markets seek a reboot in the face of existential challenges

Explainers

Carbon markets are at a crossroads. For entrepreneur Vahid Fotuhi, what happens next will influence the fate of a vast stretch of degraded mangroves along the coast of Mozambique.

A former BP executive and solar power developer based in the United Arab Emirates, Fotuhi wants to help restore these coastal wetlands and their ability to soak up carbon dioxide emissions. Done right, he believes the restoration would help reverse global warming, improve the lives of villagers living in the area and revive an invaluable natural ecosystem.

He needs a lot of money to do this and plans to get a chunk of the necessary cash from carbon offsets.

Offset agreements allow carbon dioxide emitters anywhere — from companies to consumers — to pay others, like Fotuhi’s company Blue Forest, to eliminate carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Those eliminated emissions are represented by carbon credits, also called offsets, that can be bought and sold on exchanges , more simply known as carbon markets.

Trouble is, carbon markets are a mess, some say an unfixable one. The notion that carbon emitters — be they countries, companies or individuals — can help solve climate change by paying someone else to reduce or avoid emissions is fatally flawed, critics say.

“It’s a nut that can’t be cracked, because it’s just a fantasy,” said Joseph Romm, a senior research fellow at the University of Pennsylvania Center for Science, Sustainability and the Media.

Romm’s recent 50-page analysis of the challenges facing carbon offsets concludes much of the money spent on carbon credits so far has been wasted because offsets simply provide an excuse to continue emitting carbon.

“Many things that offsets are supposedly funding today, like deploying clean energy and ending deforestation in developing countries, are crucial climate solutions — they just shouldn’t be turned into a license for developed countries and companies to keep polluting,” he writes.

Fotuhi and many others in the industry believe better designed offset markets can contribute mightily to climate solutions. Offset sales soared to as much as $2 billion annually by 2022 as more than 6,000 companieshave committed or said they will commit to net-zero emissions, up from just a few hundred companies with such commitments three years ago. An analysis by European oil and gas giant Shell and consultant Boston Consulting Group (BCG) said offsets have the potential to reach sales between $10 billion and $40 billion annually by 2030.

New projects that will eventually generate offsets continue to grow. But prices for carbon credits have fallen over the past year and fewer credits are being used recently to offset emissions in corporate plans. Both trends signal doubts over the market, industry officials say.

Virtually everyone on both sides of the offsets debate agree the industry — which has been battered for two years by media investigations and academic studies highlighting fake credits, false claims, next-to-worthless results and rampant greenwashing — is suffering a crisis of confidence.

And confidence is the lifeblood of any marketplace.

As COP28 approaches, the industry is attempting a major reboot. After years of intense activity by dozens of study groups and implementation committees, the carbon trading industry has launched fresh initiatives to raise the quality of offsets and codify what claims buyers can credibly make after purchasing them.

The industry’s hope is common standards will bring renewed confidence and allow carbon markets to become a primary vehicle for channeling desperately needed climate financing to low- and middle-income countries with few other options.

“We seek to address some of what are, quite frankly, the terminal challenges we’re facing as voluntary carbon markets,” Lydia Sheldrake, director of policy and partnerships for the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative (VCMI), told a virtual industry gathering earlier this year. The event was in preparation for COP28, where many of the reforms will be highlighted. “What we’re talking about is a wholesale transformation to really grow these into mature, multi-billion-dollar markets.”

Carbon markets come in two distinct but increasingly linked types.

Compliance markets are run by governments, which require certain carbon-emitting industries like power generators and steelmakers to participate, depending on the country. Certificates give companies the right to emit an allotted amount of carbon. Companies that emit less can sell unused certificates to others, allowing them to emit more. Governments reduce the overall number of certificates over time to restrict total emissions.

These markets are now operating in California and Washington in the United States, in China and India and across the European Union. Government-run markets now regulate about a quarter of all emissions, up from only 7% a decade ago. These government-run markets draw less criticism than the other kind of carbon market, which is entirely voluntary.

Voluntary carbon markets are far more freewheeling, loosely structured and complicated. They lack an organizer or authority and are made up of an international patchwork of companies, self-organized consortiums, private broker-dealers and project developers operating independently. The UN and some governments participate as well, but they don’t regulate or organize these markets.

Thousands of major corporations, from Nestle and Coca Cola to Delta Airlines and the biggest international oil and gas companies, have bought offsets on the voluntary market and used them to present progress toward meeting internal targets to cut their emissions to net zero.

But recently, the cloud of suspicion academic studies and media reports have cast on offsets has caused some buyers to renounce or abandon their ambitions for offsets. A few have even been sued. Prices for carbon credits have fallen sharply this year, market participants say. Shell, which conducted the study with BCG forecasting carbon markets could grow fivefold by 2030, quietly dropped its own plan to buy offsets this year.

Some industry officials and companies have pinned hopes on a growing, but still tiny, category of offsets generated by removing carbon from the atmosphere. This is done either with technology or by planting or restoring forests and agricultural land to pull carbon from the air. Just 3% of existing offsets are focused solely on carbon removal, which advocates say is easier to verify and guarantee than traditional offsets. Traditional offsets have focused on avoiding or reducing future emissions by building clean energy or preventing deforestation to preserve carbon-absorbing trees.

At COP28 next month, the UN plans to finalize a new scheme for countries and carbon offset purchasers in both the voluntary and mandatory types of carbon markets to ensure carbon credits don’t exaggerate their impact on emissions or get deployed by multiple parties at once. The UN will likely give some credits its own official stamp of approval. The UN credits would require the country in which the credit is generated to find new reductions to meet its own climate goals so that the country where the buyer is located can count the reduction in its decarbonization tally.

The UN and voluntary markets would view other credits as simply “contributions” to fighting climate change that wouldn’t be counted towards either country’s emissions reduction goals.

Alongside these changes, an array of industry groups have proposed a set of shared standards for how buyers should use carbon offsets and common guidelines for sellers. With these initiatives, the groups aim to avoid the sort of dramatic flameout a massive project in Zimbabwe recently underwent after generating $100 million selling offsets over decades that may have had little impact.

“For me it’s a roadmap,” Fotuhi said of the project in Zimbabwe. “A great case study in what not to do.”